We travel to Botswana to find out just what makes the Etsha Baskets so good

To the Source

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

<em>© L'AB/Pamono</em>

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Peter Mabeo and Katenya Phutato

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

-

Photo © L'AB/Pamono

The international design community is buzzing with talk of Africa. Cape Town was named the World Design Capital this year—the first time an African city has received this honor—and in late February the sprawling, seaside metropolis saw a record-breaking influx of journalists, designers, and dealers (and us!). Everyone endured epic flights to check out the Design Indaba conference and the Southern Guild fair, and to find out generally what’s up down there. In the news, great expectations surround forthcoming projects from starchitects, like David Adjaye’s Alara concept store in Lagos and Thomas Heatherwick’s silo-turned-art-gallery in Cape Town. We’ve also heard that a major Africa-themed exhibition is in the works at Vitra Design Museum, as well as a selling show at London’s Themes & Variations gallery—both set to open next year. It’s exciting to see the mainstream design conversation open up to embrace a continent that’s been so long overlooked.

For us, though, one of the most inspiring channels in this rising tide of African talent is the resurgence of interest in traditional Sub-Saharan crafts. Following one stream to its source—driven by our longstanding passion for exceptional artisanal work—we recently found ourselves in Botswana, where designer-editor-entrepreneur Peter Mabeo took us to meet the remarkable weavers of the Etsha villages in the Okavango Delta.

Since 1997, Peter has run his eponymous Gaborone-based studio dedicated to producing sustainable and humane furniture and décor in collaboration with local craftspeople specialized in woodwork, textiles, and basketry. “I don’t know why, but I always wanted to do something that engages the outside world… but in a way that honors Batswana heritage,” explained the enterprising, soft-spoken, and often quite funny design impresario while steering our rented 4x4 around the cattle and donkeys that peppered the solitary highway through the savannah. Over the years, he combed his country’s artisanal centers to uncover the highest quality workmanship, and then invited major designers like Patricia Urquiola and Patty Johnson to develop designs for his coterie of skilled makers. You can often find him exhibiting the results at international design events, including Salone in Milan and ICFF in New York. It’s still rare to find an African exhibitor in such venues, and Peter has done a lot to raise awareness of design work from Africa.

Hours out of Maun (the airport hub serving northwestern Botswana), Peter turned off the highway and drove us over sandy, unpaved roads through an elephant habitat to a two-room, unadorned concrete building in Etsha 6: one of thirteen villages formed by the Hambukushu people who fled violence and war in Angola in the late 1960s. There, we were introduced to the women of the Ngamiland Basket Weavers Trust, an organization by and for the region’s weavers to help them connect with buyers and pass their skills onto the next generation. Katenya Phutato, an instrumental founder and administrator for the Trust, planned a full day for us, including a fascinating weaving demonstration, a lesson in basketry connoisseurship, and an inspiring performance by the Etsha ceremonial dancers. We hadn’t really known what we would see on this trip, but for sure this was beyond our expectations.

You see baskets all over southern Africa, ornamenting the walls and tables of just about any restaurant, eco-camp, airport, or gas station you visit. It’s true that highly skilled weaving can be found in every African region; the Etsha weavers, however, are recognized to be among the very best artisans on the continent—true masters of their craft.

This particular alliance of women is adept at producing what is known as Competition Class baskets, the top tier in the elaborate grading system recognized by official basket traders. The skills and dedication involved in basket making has become a great source of village pride because the Etsha baskets consistently receive to the highest honors at the many regional and national culture festivals organized by the government to help keep these traditions alive. And the growing collectorship surrounding these baskets is playing a role as well.

The Etsha baskets come in a variety of shapes and sizes—wide-rimmed bowls and lidded hampers ranging from a few centimeters to a full meter high—always executed with the tightest, smoothest weave inside and out. Depending on the size and pattern, each basket requires weeks, months, or even years to complete. Using only the strands of mokola palm dyed with roots and leaves in a spectrum of browns and terracottas, they create a variety of intricate patterns with joy-inducing names like Forehead of the Zebra, Knees of the Tortoise, and Ribs of the Giraffe. Traditionally the baskets produced by the Hambukushu people were all white, the natural color of dried mokola. Since they moved to the Okavango Delta, however, encounters with local weavers and enthusiastic tourists led to the introduction of the now-signature multi-toned embellishments.

During the weaving demonstration, more than a dozen women carrying baskets at various stages of completion assembled in the small concrete community building, sat down on the floor, and set about doing what they do everyday. Some began at the beginning, soaking the mokola in pans of water to it make more pliable, splitting the fronds into thin strands, and binding the strands into thick cords to serve as the baskets’ understructure. Others worked at a more advanced phase of the process, selecting already dyed mokola strands to wrap around the cords, pushing them through the tiny holes they made with robust metal needles. All the while, they kept count of their stitches and cared for their youngest children who sat on their laps or crawled nearby.

The long, hot day concluded with a series of storied performances by a group of fully costumed musicians and dancers. The central figure in the troupe wore an elaborately beaded skirt embellished with animal skins and feathers. The synchronized, syncopated singing, clapping, and dancing of women in batik and leather skirts complemented his charismatic presence, as did the trio of drummers. Each dance recounted a narrative from Hambukushu life, from run-ins with lions while tending crops, to the process of overcoming sickness through medicinal and divine intervention. One of the dances even reenacted the collection of mokola for basket making, indicating how deeply entrenched and essential this artisanal tradition is among these people. For us, the performances offered a once-in-a-lifetime window into their journeys and joys, serving as potent reminders of the depth of talent that has existed in this region for so long—finally receiving much due attention from the outside world.

Thank you, Peter, for giving us the gift of these insights.

-

Text by

-

Wava Carpenter

After studying Design History, Wava has worn many hats in support of design culture: teaching design studies, curating exhibitions, overseeing commissions, organizing talks, writing articles—all of which informs her work now as Pamono’s Editor-in-Chief.

-

More to Love

Sefefo Occasional Table by Patricia Urquiola

Sefefo Long Table by Patricia Urquiola for Mabeo

Pula Table by Luca Nichetto

Kalahari Table Round by Claesson Koivisto Rune

Kalahari Atlas Stool by Claesson Koivisto Rune

Kalahari Cabinet: Four Door Unit by Claesson Koivisto Rune

Kalahari Wardrobe Medium by Claesson Koivisto Rune

Kalahari Desk with Privacy Screen by Claesson Koivisto Rune

Meradi Wardrobe by Garth Roberts

Meradi Cabinet: Two Door Unit by Garth Roberts

Tswana Folding Chair by Patty Johnson

Thuthu Table with Painted Stripes by Patty Johnson for Mabeo

Kota Tray with Painted Trim by Garth Roberts

Thusi Clothing Valet Small by Studio Noi

Seri Bowl by Garth Roberts

Seri Candle Holder for 1 Candle by Garth Roberts

Sanka Tray Single by Garth Roberts

Supa Dining Chair by Mabeo Studio

Sesana Table by Mabeo Studio

Saale Desk by Mabeo Studio

Sanka Container Large by Garth Roberts

Naledi Side Table with Weaving by Patricia Urquiola

Maun Windsor Dining Chair in Color by Patty Johnson

Medium Rothko Serving Board by Claesson Koivisto Rune

Large Rothko Serving Board by Claesson Koivisto Rune

Thuthu Stool with Painted Stripes by Patty Johnson

Peo Bowl in Panga Panga Wood by Patty Johnson for Mabeo

Folete H Platform Dresser by Garth Roberts

Sefefo Color Series Stool with Painted Trim by Patricia Urquiola for Mabeo

Sefefo Color Series Stool in Black and Green by Patricia Urquiola

Sefefo Color Series Dining Table with Painted Trim by Patricia Urquiola for Mabeo

Maun Windsor Lounge Chair by Patty Johnson for Mabeo

Maun Windsor Side Chair by Patty Johnson for Mabeo

Maun Windsor Side Chair in Matte Blue by Patty Johnson

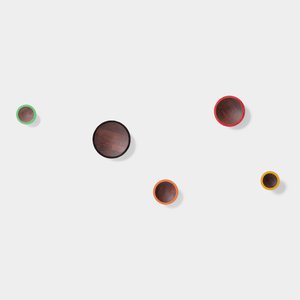

Nika Coat Hooks with Painted Trim by Garth Roberts for Mabeo, Set of 5

Peter Mabeo, our excellent tour guide

© L’AB/Pamono

Peter Mabeo, our excellent tour guide

© L’AB/Pamono