Adam Štěch visits the wonderlands of Nanda Vigo

Through the Looking Glass

Given her signature repertoire of reflective surfaces, neon tubes, gridded expanses, and fake fur, you’d be forgiven for assuming that the work of Nanda Vigo arose out of the radical design movement of the 1960s. In fact, this pioneering Italian artist-architect was creating radical interiors and objects even before the landmark debut of Superstudio and Archizoom in 1966. Her greatest influences, it turns out, were the “total environments” (gesamtkunstwerk) of modernist architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Giuseppe Terragni, and Gio Ponti—for whom she worked for several years at the start of her career. At the same time, she played a vital role in the avant-garde Zero art movement. Our friend, curator and historian Adam Štěch, was lucky enough to recently visit this visionary octogenarian in her Milan apartment and, soon after, toured one of her remaining architectural marvels. We’re so pleased to share this write up and photography from his experience.

Despite her advanced age, Nanda Vigo is still active. At the time of my visit, she enthusiastically invited me to see her latest installation at Palazzo Reale. Her apartment in the center of Milan (built in the 1970s) is a living gallery that offers surprises at every turn. Her many designs can be found through out, surrounded by a small rainforest of plants, endless mirror reflections, a turtle, and a few parrots. Green, blue, and red light tint the many chrome surfaces. This “jungle” of radical expression is a spatial manifestation of her enduring aesthetic approach and an archive of Vigo’s too often overlooked legacy.

Born in 1936, Vigo founded her studio in Milan in 1959, after she had studied at the Polytechnic in Lausanne and had spent some time in San Francisco. “I had always wanted to go to the US, but once I was there I realized that it was not a perfect place to learn and practice design,” Vigo recalls of her early years. “In America, it was more about art or architecture, but a true design scene was missing. It was not so easy to develop a project and collaborate with artisans there as in Italy. So I came back to Milan.” Upon her return, she made friends with an older generation of architects, most notably Gio Ponti, and became even closer to leaders of the avant-garde, especially the artists around the legendary Azimut Gallery. Her tight and talented circle included Lucio Fontana, Enrico Castellani, and Piero Manzoni, with whom she lived until his tragic, premature death in 1963. She was never a pureblooded designer, but presciently stood on the edge of applied and fine art, one of the essential themes that would define the radical design movement a few years later.

Together with the celebrated Zero group, founded by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene in 1957, Nanda exhibited in Germany, the Netherlands, France, and the US. She became known for her Cronotopo aluminum and glass optical sculptures. At the same time, she began to produce architectural projects that were startling for their time, such as the high-rise cemetery in Rozzano (1959) and the all-white Zero House in Milan (1959-62). Looking back on that time, she says, “I was following the vision of the great Gio Ponti; he approached spaces in a global way, from the small spoons to the art. I always saw architecture, design, and art together as one in my projects.”

For Vigo, light was the key to her boundary breaking vocation. “When I was seven years old, I first discovered the idea of beauty by looking at Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa del Fascio in Como,” Vigo remembers. “The beauty, for me, was the light. It changed the architecture throughout the day. So that’s why I decided to design lamps.” Her minimalist designs for Arredoluce in the 1960s and ’70s introduced a new concept for lighting by combining chromed steel with innovative technological features, culminating in the Golden Gate Floor Lamp (1969-70), which was one of the first halogen lamps in Italy.

One of Vigo’s few still-preserved interiors is the house created for art patron and collector Giobatta Meneguzzo in the town of Malo. While the house itself, called Lo Scarabeo Sotto La Foglia (The Beetle Under the Leaf), was designed by Ponti in 1964, the interior design was entrusted to Vigo. “Meneguzzo knew that I was friends with Gio Ponti,” says Vigo. “So when [Ponti] asked him if I could design the interior of his house, he agreed.” The resulting monochrome space lined with ceramic tiles and gray fake fur included artworks by Fontana, Castellani, Julio Le Parc, Raymond Hains, and more.

Vigo designed several similarly mesmerizing, art-filled residential interiors during the 1970s, for instance Casa Museo Remo Brindisi in Lido di Spina near Ravenna, which was built in 1973 and is open now in its original form as an art gallery. “Many important people from the art scene knew me, and they asked me to design special apartments for them,” Vigo says. “For example, my Black Apartment [Casa Nera] was designed according to the client’s idea that good artwork should be seen lit by just the a flame of a candle. So I designed everything dark and used only atmospheric lighting. Another apartment was all yellow [Casa Gialla], because it was for a client from southern Italy, and he wanted to be reminded of the colors of home.” Vigo tells me more about her concepts for apartments without windows, illuminated with colorful lights and neon, layered with with glossy surfaces, and, of course, punctuated by the art that these spaces of desire were created for.

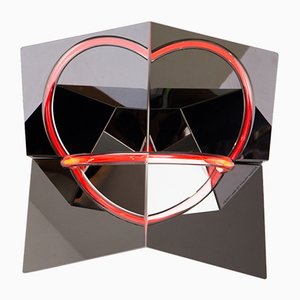

Vigo’s later works from the 1980s and ’90s moved away from monochromy toward a more eclectic expression, influenced by the freshly fashionable postmodern theory. As the designer began to work more with colors, her new designs brought her closer to the boisterous experiments of the Memphis and Alchimia groups. Her Light Tree series, made of colored glass sheets and steel profiles, were particularly on trend for their day.

Since the early 1980s, Vigo has continued to exhibit all around the world and participate in important cultural events, such as Venice's 40th Biennale in 1982. In 1997, she curated the show Piero Manzoni—Milano et Mitologia in Palazzo Reale, and since 2006 her work has been in the permanent collection of the Triennale Design Museum. In 2014/2015, her works were on display in the Guggenheim Museum, New York, and in the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, as part of the events celebrating ZERO. Although her work is most often found in galleries, she has frequently designed products for brands such as Arredoluce, Driade, Flou, Glas Italia, and Kartell. Vigo’s most famous furniture design remains the Due Piu’ Chair for Conconi (1971), which, true to her style, marries modernist design with vanguard art—tubular steel in reference to Bauhaus functionality and fur upholstery with a nod to ’60s-era Pop Art.

For nearly 60 years, Vigo has remained steadfast in her multifaceted, all encompassing vision. From the 1960s onward, she’s created lamps and furniture that were conceived as artistic objects in the spirit of kinetic art and the spatially driven philosophy of group ZERO. She approached her impressive interiors as total-art installations, always aiming at transformative aesthetic experiences and pure life enjoyment. Along the way, she’s helped to foster a sense of playfulness, spiritual symbolism, and iconoclasm in design, while holding a unique position both inside and outside the radical design movements of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. Still today we are feeling the effects of that generation’s efforts, as the boundaries between the real practicalities of everyday life and the imagination of art have completely blurred.

-

Text & photography by

-

Adam Štěch

Adam is a Prague-based editor and curator. He cofounded OKOLO creative collective and writes for publications like Wallpaper, Coolhunting, Domus, and Modern. He's also collaborated with Phillips de Pury, SightUnseen, Disegno, and Architonic.

-