Rasmus Graversen of Fredericia on the legacy of Danish modernist Børge Mogensen

Quiet Magic

-

Designer Børge Mogensen

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Inside the home that Mogensen designed for Andreas Graversen

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Mogensen's Copenhagen home

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Børge Mogensen with the design team at Fredericia

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Window detail inside the home Mogensen designed

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Spanish Chair by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia (1958)

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Børge Mogensen's Spanish Chair (1958) gets put to the test

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Børge Mogensen with his Model 2213 Sofa

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Model 2213 Sofa by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Model 2252 Sofa by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

-

Bench by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

Fans of Danish modernism will no doubt be familiar with the names Børge Mogensen and Fredericia. For those in need of a crash course: Mogensen was a student of Kaare Klint in Copenhagen and one of a handful of designers who popularized modernism in Denmark and paved the way for the growing international obsession with midcentury Danish design; Fredericia is one of the most respected furniture manufacturers in the Danish tradition of quality craftsmanship and sophisticated aesthetics, with a history stretching back over a century.

Both the designer and the manufacturer are entitled to their stellar reputations in their own right. But if you look deeper into the loyal, creative partnership between Mogensen and Fredericia, hints of a collaborative alchemy emerge. We spoke with Rasmus Graversen—Product and Design Manager at Fredericia—to learn more about Mogensen’s imposing intellectual and aesthetic legacy and how it continues to guide the company today, nearly 50 years after Mogensen’s death.

Fredericia was established by N. P. Ravnsø in 1911 and was run by the Ravnsø family for several decades until Andreas Graversen took over the company in 1955. According to Rasmus Graversen, his grandfather stipulated one condition to his taking over the then struggling Fredericia Furniture: that Børge Mogensen also come on board. Andreas Graversen and Mogensen knew each other through the cabinetmaker Tage Christensen and had also worked together at the Danish Consumers Coöperative Society (FDB). Graversen wanted the designer’s “unpretentious, pure, and honest” design ethos to be the guide for the future of Fredericia. He travelled to Copenhagen to convince Mogensen to join the new venture as head of design and committed to rebuild Fredericia solely around Mogensen’s designs.

The collaboration immediately proved fruitful; Mogensen’s first design for Fredericia—the Model 201 Sofa (1955)—is today considered an iconic landmark and, following a relaunch under the name No 1. Sofa in 2014, it became the company's most successful sofa. But what developed between Mogensen and the Graversen family—first Andreas Graversen, then his son Thomas Graversen who joined Fredericia in the late '80s, and recently the third generation; Rasmus Graversen—went much far beyond the standard business relationship. Rather, the collaboration seeded a new way of producing furniture; one that seamlessly blended working and living; one in which the designer and the CEO’s homes and families became as crucial to the development of new products as the factory and its craftspeople.

In pursuit of ways to more fully inhabit his modernist ideology, Mogensen designed an entire home for himself in Copenhagen, from the architecture to the interior fittings and bespoke furnishings—and, perhaps as a gesture of friendship, or perhaps as an expansion of their creative commitment to each other, he also designed a home for his business partner Andreas Graversen. Both Thomas and Rasmus Graversen grew up in and around this home, experiencing Mogensen’s vision as their earliest—and most subliminal—introduction to design.

“Mogensen’s designs are very much about how the materials affect each other. In the house the leather and wood furniture was combined with raw brick walls and stone floors. It was very inspired by both Mediterranean and Japanese architecture—combined with Danish functionalism” recalls Rasmus Mogensen. “Everything was custom fitted to the house and combined with certain fine art (Albert Mertz, Palle Nislesn, Svend Wiig Hansen), ceramics (Gertrud Vasegaard), and tableware (Grethe Meyer).” The result was an all-encompassing aesthetic gestalt “where everything might seem subtle standing alone, but in combination the impression became very powerful—and, first and foremost, very nice to be in” Rasmus Graversen remembers. It was a lesson that stuck: “This appreciation for simple forms and material feeling is inherent in everything my father and I do today.”

Even more than the aesthetic harmony, though, it was the ethos of practical, long-lasting, and truly functional furniture and interiors that made the most impact. “The house was not for show, but really for living. So even though the furniture is expensive, we were allowed to use it as intended—in everyday life. And seeing how Mogensen’s furniture became even more beautiful in use is really inspiring for me today.”

"Living laboratories" is the apt phrase that Rasmus Graversen uses to describe Mogensen and his grandfather’s approach to integrating their living spaces and the everyday life with their families into the design process. He explains, “Andreas and Børge always put their furniture to use [in their own homes] before launch, so they were sure the product was good. This tradition has been continued by my father; he always brought prototypes to our house in order to see how the furniture would perform when put to real use.” And it obviously paid off. In 1971, Andreas Graversen and Børge Mogensen were jointly awarded the prestigious Danish Furniture Prize. A year later, following Mogensen's untimely death at 58, he was appointed the Honourary Royal Designer for Industry at the Royal Society of Arts in London—just one of a number of posthumous awards.

The principles that Mogensen and Andreas Graversen lived and worked by when their collaboration began more than half a century ago live on at Fredericia. Although the company has had successful collaborations with other legendary designers, notably including Nanna Ditzel during a long period in the late 20th century, Rasmus Graversen insists that “Mogensen is the fundament for how we evaluate what is good furniture.” He goes on to say that at Fredericia, “we appreciate the art of proportions. Not everyone is good at that but good designers, in our opinion, master proportions more than anything else. A good technical design idea is not enough.” Mogensen’s focus on material and how combinations of material communicate is at the heart of Fredericia’s approach to furniture, even as the company has expanded its repertoire to work with contemporary designers like Jasper Morrison, Cecilie Manz, and Shin Azumi.

Times have changed, of course, and both materials and the technologies available to work with them have evolved over the last half century. The Mogensen-Fredericia collaboration was deeply rooted in the latter’s competence with solid wood. Mogensen even adapted his designs to fit Fredericia’s machines and manufacturing processes. These days, robotic production methodologies have blown the roof of what is possible in working with both traditional and new materials. Rasmus Graversen explains that Mogensen always shied away from working with steel or plastic, apparently saying that he would leave that to the next generation of designers. Well, the next generation is well and truly here, and Fredericia is engaging both with those contemporary designers and the contemporary materials and methodologies that they favour—but always under the ever-present influence of purist, Børge Mogensen.

“With the Pato Chair we have tried to adapt some of the values of Mogensens designs regarding simplicity and material feeling to the 21st century archetype: the plastic stacking chair,” Graversen says. It was a long process to create a plastic surface that, as Graversen puts it, “we would allow in the same room as Mogensen’s beautiful natural material designs.” Rather than this being a constraint, however, Graversen enthuses that “it is nice to have this test when you do the new furniture; does it stand the test when placed beside some of our classics?” It’s a question that really means something in the context of Fredericia’s design pedigree. It may not mean that all of the company’s new pieces fall within the boundaries of Mogensen’s functionalist design philosophy but they certainly need an impressive design integrity in order to hold space beside his design achievements, which, as Graversen so eloquently puts it, “have an almost monolithic calmness that is hard to beat.”

More to Love

Model 2213 Sofa by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia, 1960s

Mid-Century Model 2254 Lounge Chairs with Ottomans by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia, Set of 4

Model 227 Easy Chairs with Footstool by Borge Mogensen for Fredericia, 1960s, Set of 2

Lounge Chair & Ottoman by Børge Mogensen, 1960s, Set of 2

Vintage Oak J39 Dining Chairs by Børge Mogensen for FDB Mobler, Set of 4

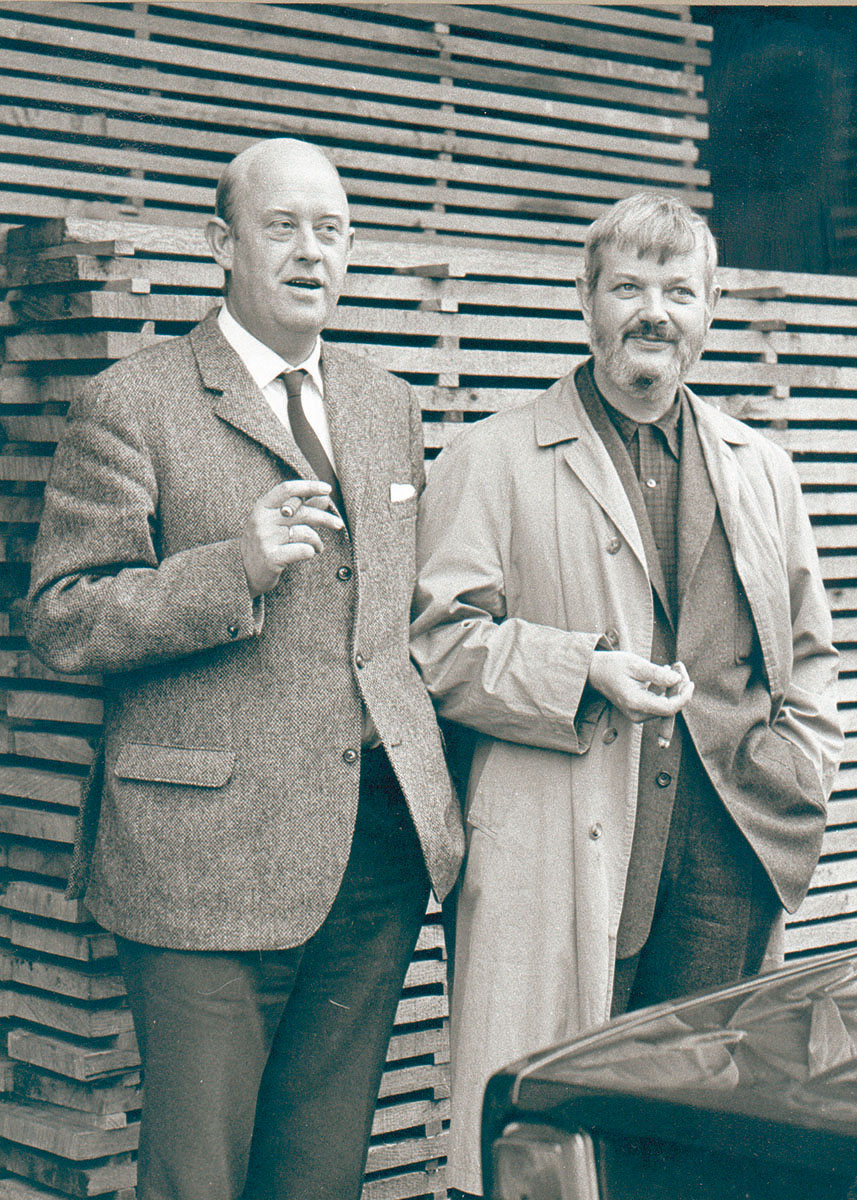

Andreas Graversen and Børge Mogensen

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

Andreas Graversen and Børge Mogensen

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

Spanish Dining Chair by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia

Photo courtesy of Fredericia

Spanish Dining Chair by Børge Mogensen for Fredericia

Photo courtesy of Fredericia